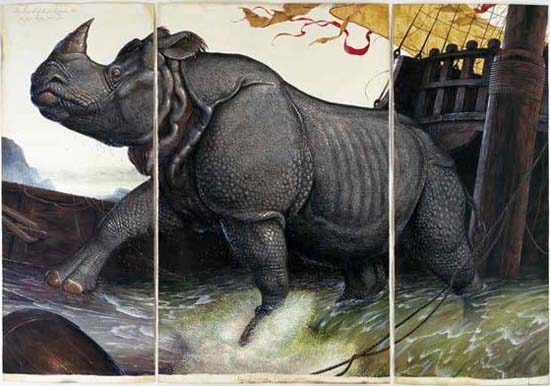

Message à Philippe De Jonckheere à propos de son rhinocéros: «Tu sais que Dürer avait fait à pied le chemin de Munich à Rome pour aller dessiner de visu le premier rhinocéros ramené en Europe, et que la gravure tirée de son dessin est probablement le premier best-seller de l’histoire de l’imprimerie? – et qu’on a ensuite rajouté le rhinocéros sur les réimpressions de Pline, qui se basait sur les récits des légionnaires revenus d’Afrique, et en avait conçu la licorne en mêlant un peu tout – mais pour ceux du 16ème siècle, si c’était chez Pline on pouvait ajouter, mais pas corriger: primauté du livre sur le réel – et la phrase de Rabelais: “Comme assez sçavez, que Africque aporte tousiours quelque chose de nouveau”, où Flaubert dit que chaque fois qu’il lit cette phrase, il voit des hippopotames et des girafes…» Oui mais voilà: ni Dürer ni le rhinocéros ne sont jamais allés à Rome, j’avais simplifié l’histoire. = My earlier message to Philippe De Jonckheere concerning his rhinoceros: Do you know that Dürer went from Munich to Rome on foot in order to see and draw the first rhinoceros ever brought to Europe, and that the engraving based on his drawing became the first bestseller of the history of printing? – and that this rhinoceros was then also included in the reprints of Pliny based on the reports of the Roman legionaries returning from Africa, which even led to the birth of the idea of the unicornis, thus mixing everything a little bit – but for the 16th century one could add things to Pliny, but not change things in it: voilà the priority of the book above the reality –, and the saying of Rabelais: “As you well know, there is always something new coming from Africa,” about which Flaubert says that whenever he reads it, he always sees hippos and giraffes…” Well, I was mistaken. Neither Dürer, nor the rhinoceros ever reached Rome. I have simplified the story.

Message à Philippe De Jonckheere à propos de son rhinocéros: «Tu sais que Dürer avait fait à pied le chemin de Munich à Rome pour aller dessiner de visu le premier rhinocéros ramené en Europe, et que la gravure tirée de son dessin est probablement le premier best-seller de l’histoire de l’imprimerie? – et qu’on a ensuite rajouté le rhinocéros sur les réimpressions de Pline, qui se basait sur les récits des légionnaires revenus d’Afrique, et en avait conçu la licorne en mêlant un peu tout – mais pour ceux du 16ème siècle, si c’était chez Pline on pouvait ajouter, mais pas corriger: primauté du livre sur le réel – et la phrase de Rabelais: “Comme assez sçavez, que Africque aporte tousiours quelque chose de nouveau”, où Flaubert dit que chaque fois qu’il lit cette phrase, il voit des hippopotames et des girafes…» Oui mais voilà: ni Dürer ni le rhinocéros ne sont jamais allés à Rome, j’avais simplifié l’histoire. = My earlier message to Philippe De Jonckheere concerning his rhinoceros: Do you know that Dürer went from Munich to Rome on foot in order to see and draw the first rhinoceros ever brought to Europe, and that the engraving based on his drawing became the first bestseller of the history of printing? – and that this rhinoceros was then also included in the reprints of Pliny based on the reports of the Roman legionaries returning from Africa, which even led to the birth of the idea of the unicornis, thus mixing everything a little bit – but for the 16th century one could add things to Pliny, but not change things in it: voilà the priority of the book above the reality –, and the saying of Rabelais: “As you well know, there is always something new coming from Africa,” about which Flaubert says that whenever he reads it, he always sees hippos and giraffes…” Well, I was mistaken. Neither Dürer, nor the rhinoceros ever reached Rome. I have simplified the story. Ernst Gombrich in his Art and illusion (1960) – that in my university years, when I still led a list of those ten books that influenced me the most, I included in it – says that the artist does not draw what he sees but what he knows. He unconsciously formulates the view with the help of the schemes he had learnt, and thus however realistic the representation might appear to his contemporaries, a later generation using different schemes will regard it rigid and schematic.

The same idea leads the pen of the Hungarian classical philologist of international renown János György Szilágyi in his Legbölcsebb az idő (Time is the wisest) (1978, 1987). In this overview of the centuries long history of the falsification of ancient vase paintings he points out that the fakers of a generation were exposed always when the visual schemes applied by them and regarded as self-evident by their generation became obviously conspicuous for the next one.

It is quite possible that Egyptians enjoyed as fresh and original representations of the nature those images which appear as rigid hieratic frescoes to us, for whom their schemes are obvious and archaic.

Gombrich illustrates this argument with one of the earliest European drawings of which we know that it was explicitly made “after nature.” In the famous sketch book of the 13th-century French architect Villard de Honnecourt we read to the right of the lion below: “Voici 1 lion si com on le voit par devant. Et sacies bien qu’il fu contrefais al vif.” (Here you are a lion, frontally seen. And you must know that I drew it after nature.) We have no reason to doubt in the truthfulness of the renowned architect who toured all Europe, and had the possibility of seeing living lions in more than one princely court. Nevertheless to us his drawing resembles more those Gothic lion statues whose masters never saw a living lion than to the animal we know from the zoo or from photos and films.

Gombrich’s other example is the engraving Dürer made in 1515 on the rhinoceros of the pope.

The complex manoeuvres of power politics which led this rhinoceros from hand to hand from India to Italy were described in detail by Silvio Bedini, keeper of the rare books of the Smithsonian Institute in his brilliant The papal pachyderms (1981, Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society). The sultan of Cambay donated the animal to the Portuguese governor of Goa in order to sweeten the bitter pill, that is the refusal of the Portuguese territorial claims. The governor sent it further to Lisbon in order to allay the anger of King Manuel I on the failure of the mission. The king sent it to Pope Leo X to Rome in order to secure his benevolence as an arbiter concerning the border line between the Portuguese and Spanish expansion in South-Eastern Asia. Only the rhinoceros had no profit from all that. The ship with which he was carried in February 1516 to Italy, was caught by a storm, and the rhinoceros,

hanc inusitate feritatis belluam, quae in arena amphitheatri elephanto ad stupendum certamen committi debuerat, Neptunus Italiae invidit et rapuit, quum navigium, quo advehebatur, Ligusticis scopulis illisum, impotentis tempestatis turbine mersum periisset; eo graviore omnium dolore, quod bellua, Gangem et Indum altissimos terrae patriae fluvios tranare solita, in ipsum littus supra portum Veneris, vel arduis saxis asperrimum, enatare potuisse crederetur, nisi, compeditus cathenis ingentibus, nihil proficiente evadendi conatu, superbo maris Deo cessisset.

this animal of unusual ferocity, which would have confronted even the elephant in a marvellous fight on the sand of the amphitheatre, was taken away out of envy by the Neptun of Italy when the ship carrying it bumped against a rock at the Ligurian shore and went down in the waves of the sea lashed into fury, to a great sorrow and pain of everyone who know that this beast is able to swim across the Ganges and the Indus, enormous rivers of his native land, and thus could have easily swimmed out to the seashore rocks above the haven of Venus, were not his feet linked by heavy chains; but so, having no use of his swimming knowledge, rendered itself to the arrogant god of the sea.

– writes in the Gallery of famous men (1548) Paolo Giovio, historian of the pope and author of the immortal History of Italy, who will play later an important role in keeping and forming the visual memory of the rhinoceros.

However, to the good luck of the European visual tradition, during the Lisbon months a learned description, and even a sketch was made on the rhinoceros from the pen of the Moravian merchant Valentim Fernandes living in Portugal, to which we will return in a later post. The Italian translation of the description addressed to “the merchants of Nuremberg” is conserved in the Magliabechiana library of Florence. Of its original German text has only survived that part which Albrecht Dürer, who prepared his engraving of the rhinoceros – “the most influential European animal representation,” as T. H. Clarke writes in his The rhinoceros from Dürer to Stubbs, 1515-1799 (1986) – on the basis of this description and sketch, included at the upper edge of his work:

Nach Christiegeburt, 1513. Jar Adi 1. May hat man dem grossmechtigisten König Emanuel von Portugal, gen Lysabona aus India pracht, ain solch lebendig Thier. das nennen sie Rhinocerus, Das ist hie mit all seiner gestalt Abconterfect. Es hat ein farb wie ein gepsreckelte [sic] schildkrot, vnd ist von dicken schalen vberleget sehr fest, vnd ist in der gröss als der Heilffandt, aber niderichter von baynen vnd sehr wehrhafftig es hat ein scharffstarck Horn vorn auff der Nassen, das begundt es zu werzen wo es bey staynen ist, das da ein Sieg Thir ist, des Heilffandten Todtfeyndt. Der Heilffandt fürchts fast vbel, den wo es Ihn ankompt, so laufft Ihm das Thir mit dem kopff zwischen die fordern bayn, vnd reist den Heilffanten vnten am bauch auff, vnd er würget ihn, des mag er sich nicht erwehren. dann das Thier ist also gewapnet, das ihm der Jeilffandt [sic] nichts Thun kan, Sie sagen auch, das der Rhinocerus, Schnell, fraytig, vnd auch Lustig, sey.

In the year 1513 after Christ’s birth, on 1. May there was brought from India to Lisbon to the mighty King Emanuel of Portugal such a living animal, that they call rhinocerus. It is reproduced here in its complete form. Its color is like a speckled turtle, and it is covered very securely with thick scales, and in size it is like the elephant, but shorter in the legs and very much prepared for fighting. It has a sharp strong horn on the front of the nose, which it takes to whetting wherever there are stones. It is a triumphant animal, the elephants’ deadly enemy. The elephant fears it terribly, because when he comes upon it, the animal runs at him with the head between the front legs, and tears the elephant’s belly from beneath, and kills him, while this cannot defend himself. For the animal is so well armed, that the elephant can do nothing to him. They also say that the rhinocerus is a quick, glad-tempered, and even merry animal.

Dürer: The rhinoceros, 1515. This is the second edition of the engraving, made in the same year as the first one, with the only difference that the first edition published the text in five lines instead of six.

Dürer: The rhinoceros, 1515. This is the second edition of the engraving, made in the same year as the first one, with the only difference that the first edition published the text in five lines instead of six.We do not know how detailed and true to life was the sketch sent to Nuremberg together with the letter of Fernandes. It must caution us anyway that the same or a similar sketch also arrived to Rome, where the Florentine physician Giovanni Giacomo Penni published a description in verse about the rhinoceros well in advance before it left Lisbon for the papal court. With the loss of the animal, however, this publication also lost its raison d’être, and its propagation stopped. It has survived in one single copy, today conserved in the Colombina library of Seville, whose special feature is that on its last page there was noted by the hand of Christopher Columbus himself: “Este libro costó en Roma medio quatrain por nouiembre de 1515 / Esta registrado 2260” (I purchased this book in Rome in November 1515 for half quatrain. This is copy number 2260).

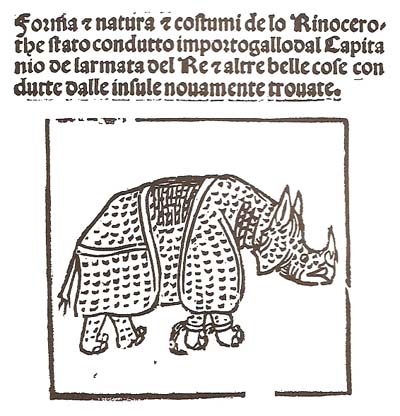

Giovanni Giacomo Penni: The form, nature and customs of the

Giovanni Giacomo Penni: The form, nature and customs of the rhinoceros taken to Portugal by the captain of the

King’s fleet, as well as a lot of beautiful

things coming from the

newly found

islands

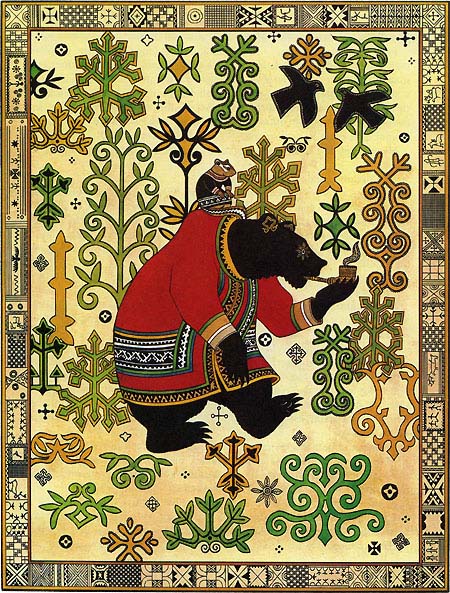

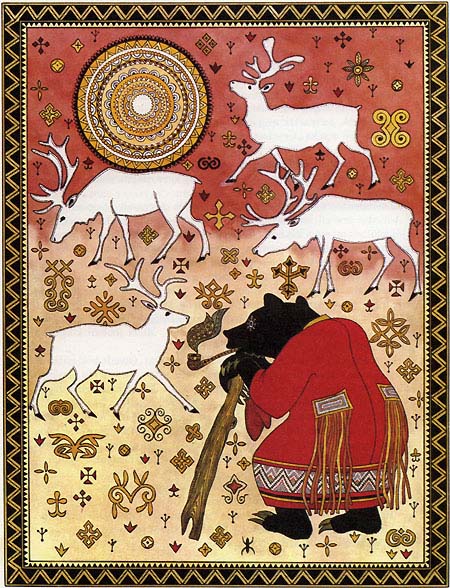

If the sketch sent to Nuremberg was similar, then Durer had plenty to add to it from his own knowledge of zoology, anatomy and proportions, from the description, and – as Gombrich stresses it – from the contemporary pictorial tradition and dominant visual schemes. He perceived the skin of the rhinoceros folded in hard plates as a kind of a knight’s armor, like the one worn by contemporary war-horses, following Fernandes’s expression gewapnet ‘armed.’ He covered both the armor and the feet of the animal with the scales mentioned by Fernandes, like those of the dragons, and he also articulated “the armor’s side plate” with a pattern recalling the dragon’s wing. He inserted between its two shoulder-blades a small horn – it is not clear whether he misunderstood something on the sketch, or he simply had to find a proper place for the “second horn” mentioned by Pliny, to which we will return in a next post – which protrudes from the middle of a small knob like the thorn in the middle of the knight’s shield keeping away the enemy in a hand-to-hand combat. And finally he covered the whole surface of the animal with a finely chiselled decoration in the spirit of the contemporary German engraving tradition.

The image created in this way is, however, not only extremely compact, powerful and convincing, but it is also much closer to reality than what could have been expected in such circumstances. Was Fernandes’s sketch this much better than the drawing of Penni? Or there were some additional visual sources available to Dürer on the rhinoceros? In the next post we will examine such a possible source.