This postcard was recently published on a Russian historical forum. According to its date it was written on 9 December 1945 in the Bessarabian – today Southern Ukrainian – Khotin, with the following text:

Хотин, Бессарабия, 9/XII-45 Дорогая мамочка! Поздровляю тебя с Новым 1946 Годом! Желаю здоровья и счастья! До скорой встречи дорогая мамочка! Лев. | Khotin, Bessarabia, 9 December 1945 Dear Mother! I greet you in the New Year of 1946! I wish you good health and happiness! See you soon, dear mother! Lev. |

The postcard was most probably written by a soldier of the Soviet army occupying Bessarabia. This is plausible not only because of the historical circumstances – Bessarabia, which in 1918 had joined Romania from the Russian Empire, then in June 1940, in terms of the secret appendix of the Molotov-Ribbentropp Pact it fell to the share of the Soviet Union, in July 1941 it was recaptured by Romania with the help of the Wehrmacht, and in August 1944 it was occupied for good by the advancing Red Army –, but also because the postcard was delivered without a stamp, as it was usual within the Red Army. But what is the castle on it and mainly why was it printed with the Hungarian text “Levelező-Lap”, that is, “Postcard”?

Khotin, from where the mail was sent has a gorgeous Medieval castle, built above the strategical pass of the Dniester in 1400 by Prince Alexandru cel Bun (1400-1432) of Moldova. Two good photo series on the pictorial castle have been published by Tim Arbaev (1 and 2). Sergej Klimenko has offered a detailed building history and a ground-plan (another version here), an Ukrainian tourist site has published some of its old views, and also the copperplate illustration of the Polish-Turkish battle of Khotin of 1673 displays the fortress in the left upper corner. But this castle is surely not identical with the ruin to be seen on the postcard.

Khotin, from where the mail was sent has a gorgeous Medieval castle, built above the strategical pass of the Dniester in 1400 by Prince Alexandru cel Bun (1400-1432) of Moldova. Two good photo series on the pictorial castle have been published by Tim Arbaev (1 and 2). Sergej Klimenko has offered a detailed building history and a ground-plan (another version here), an Ukrainian tourist site has published some of its old views, and also the copperplate illustration of the Polish-Turkish battle of Khotin of 1673 displays the fortress in the left upper corner. But this castle is surely not identical with the ruin to be seen on the postcard.

Another possibility that comes to mind is the castle of Visegrád, as seen from the side of the great 13th-century donjon, the so-called Salamon Tower. But only for a short moment. In fact, the donjon of Visegrád is much shorter, and neither the wall in front of it is the regular rondella represented on the postcard.

Another possibility that comes to mind is the castle of Visegrád, as seen from the side of the great 13th-century donjon, the so-called Salamon Tower. But only for a short moment. In fact, the donjon of Visegrád is much shorter, and neither the wall in front of it is the regular rondella represented on the postcard.

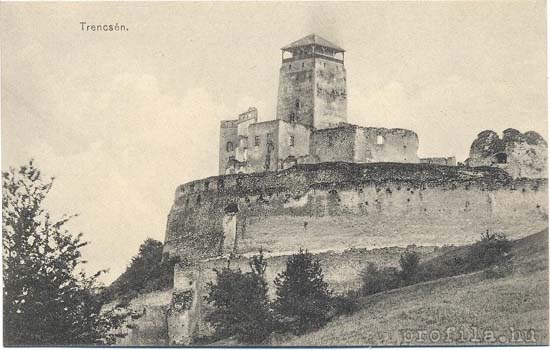

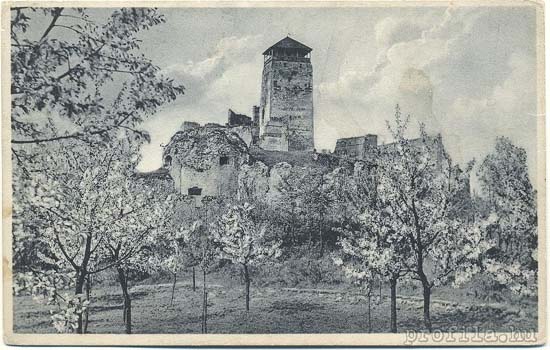

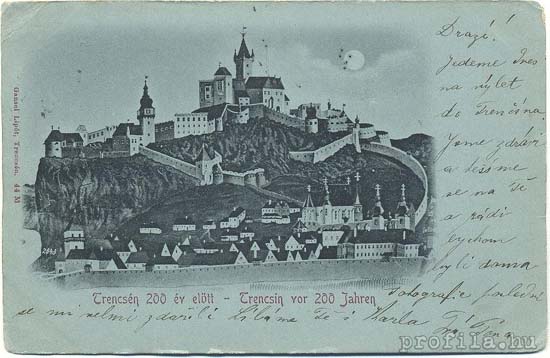

You think of all these possibilities of course only because on the small version of the picture published in the forum you do not immediately discover the small and worn inscription in the lower left corner: “Trencsén”, that is, Trenčín in Northwestern Slovakia, along the Váh river.

But even after discovering the inscription, you will have doubts. Because the castle of Trenčín is absolutely not like these scanty wall remains on the postcard. But like this:

But even after discovering the inscription, you will have doubts. Because the castle of Trenčín is absolutely not like these scanty wall remains on the postcard. But like this:

These pictures attest that the castle of Trenčín is one of the most intact medieval fortresses in Slovakia. However, going back a little bit in time, and browsing among pre-WWI postcards, you will have a totally different impression.

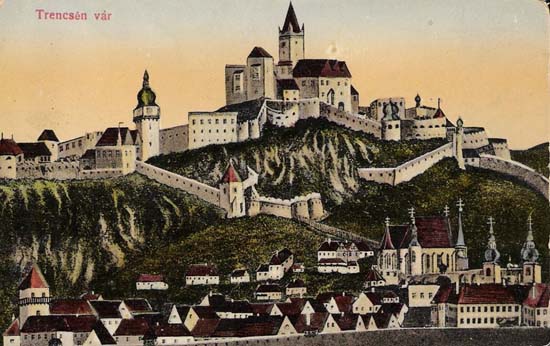

True, we also find some postcards from the same period which represent the castle just as gorgeous as it is now:

However, this view – as it is revealed by the inscriptions of other similar postcards – is only the reconstruction of a two centuries earlier situation:

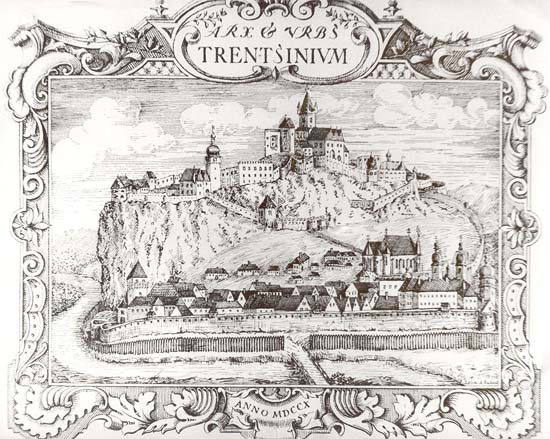

And the source of the reconstruction is a copperplate view of the castle and town of Trenčín from 1710:

The castle of Trenčín which since 1594 was in the possession of the Illésházy magnate family, looked like this until the end of the 18th century. On 11 July 1790, however, it was competely burnt out. The remains of its walls were conserved in the 1890s: that is the situation represented in the early 20th-century postcards.

The castle gained a new importance after 1920 when this northern part of the former Hungary was allotted to the freshly established Czechoslovakian state. The reason of the new interest was that in 1293 the Hungarian oligarch Matthew Csák had occupied the castle with force and made it the center of his estates that he kept increasing (seizing, among others, also Visegrád) by fishing in troubled waters in the confused years following the change of the royal dynasties of Hungary after 1301. Post-1920 Czechoslovakian historiography interpreted this episode as a first attempt to create a Slovakian state independent from the kings of Hungary, and consequently they laid great stress on the historical role of the castle. In 1952 the fortress of Trenčín was declared a first class monument, and they started its complete restoration – which in the practice meant a reconstruction of its state represented on the engraving of 1710.

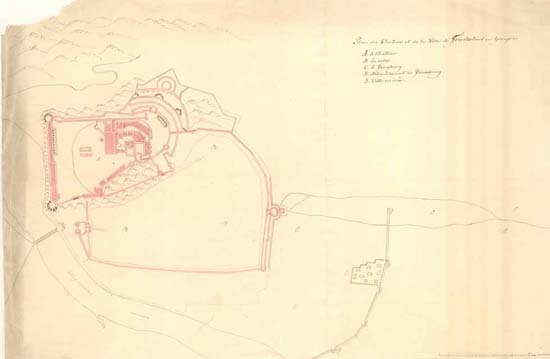

A 17th-century plan of the castle of Trenčín in the Krigsarkivet of Stockholm.

A 17th-century plan of the castle of Trenčín in the Krigsarkivet of Stockholm.(On the plans of the Hapsburg castles kept in the archive of Stockholm

see: György Kisari Balla: Törökkori várrajzok Stockholmban, 1996

[Fortress plans of the Turkish period in Stockholm])

Thus the postcard in fact represents the castle of Trenčín as it looked in the first half of the 20th century. Now the question is: why did the Soviet soldier send a postcard of Trenčín from Khotin, lying eight hundred kilometers away?

The question is further complicated by the Hungarian language of the printed postcard. Following the first Vienna Award (2 November 1938) which adjudged to Hungary the territories of Czechoslovakia with a Hungarian ethnic majority, Trenčín did not fell to Hungary but became part of the independent Slovakia. It is highly improbable that any postcard in Hungarian was published there at that time.

Political map of the Pannonian Basin after the two Vienna Awards (1938, 1940).

Political map of the Pannonian Basin after the two Vienna Awards (1938, 1940).We have indicated the places of the three castles mentioned in the post.

Furthermore, the back side of the postcard also has the name of the publisher: Gansel Lipót, Trencsén. According to the printers’ database of the Hungarian National Library, the Gansel press worked between 1850 and 1913 in Trenčín. It was a small press, editing mostly local publications and postcards.

This means that the Soviet soldier sent from Khotin a postcard that had been published more than thirty years earlier in another country and had not been in circulation for at least twenty-five years.

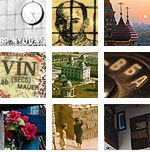

It is an enigma how he laid hands on such a postcard. However, a possible solution is suggested by two cards of another Soviet soldier published on another Russian forum.

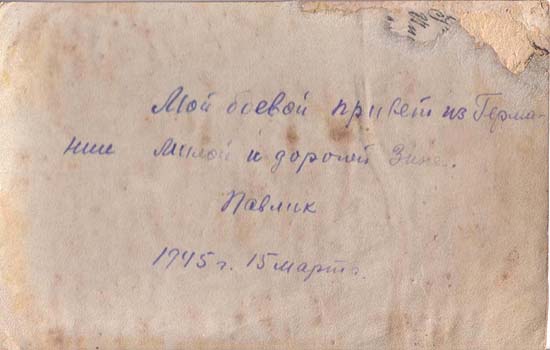

Мой боевой привет из Германии Милой и дорогой Зине. Павлик 1945 г. 15 марта. | My military greetings from Germany to the sweet and dear Zina. Pavlik 15 March 1945. |

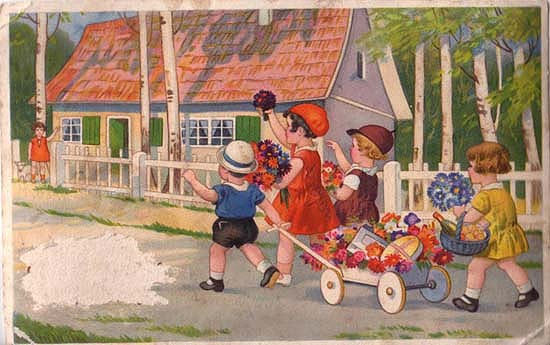

Милой и дорогой ли… Лидочке от папы. Из Германии 1945 г. 20 марта. | To the sweet and dear […] Lidochka from her Daddy. From Germany, 20 March 1945. |

The two postcards had been published in Germany, first written in German, canceled with a German postmark, and in all probability German was the original postage stamp too which was removed already in the Soviet Union as a philatelistic rarity. The Soviet soldier who probably found the postcards in the house of the original German addressee or among the ruins of it, stuck an empty paper on their back side and sent them with his own greetings: the girls collecting cherry blossoms to his wife and the children playing with the cart to his little daughter.

In fact – they write on the Russian forum as an explanation of this case –, postcards, which had been popular in the cities of pre-Revolution Russia, completely disappeared in the Soviet Union between the two wars. Only during the Great Patriotic War they started to publish postcards again, with patriotic artworks and for agitation purposes. Thereby they woke up a taste for postcards in people, but the culture of their use was not yet established. Its essence was a nice picture following the personal message, just any picture that was available. It was no problem if it represented a place different from where it was sent from. Especially if the distance between the two places was negligible in respect to the distance separating the soldier from his home.

3 comentarios:

Interesting posting. Just wanted to share a video I came across: A TIZEDES MEG A TÖBBIEK - Katyusa seems like a clip from a Hungarian movie. What is this story about?

This is one of the great Hungarian war movies (“The corporal and the others”, 1965). It is a comedy about five Hungarian soldiers who escape their regiment, compelled by the Germans to retreat with them and to defend Berlin against the Red Army. After several gruesome adventures they finally join up the Russians and become partisans. The film, performed by the greatest contemporary actors, was the hit of the 60s.

An interesting mystery. I do wish they'd restore the original roof of the Trenčín tower, though. The later one looks like a camp tower.

Publicar un comentario