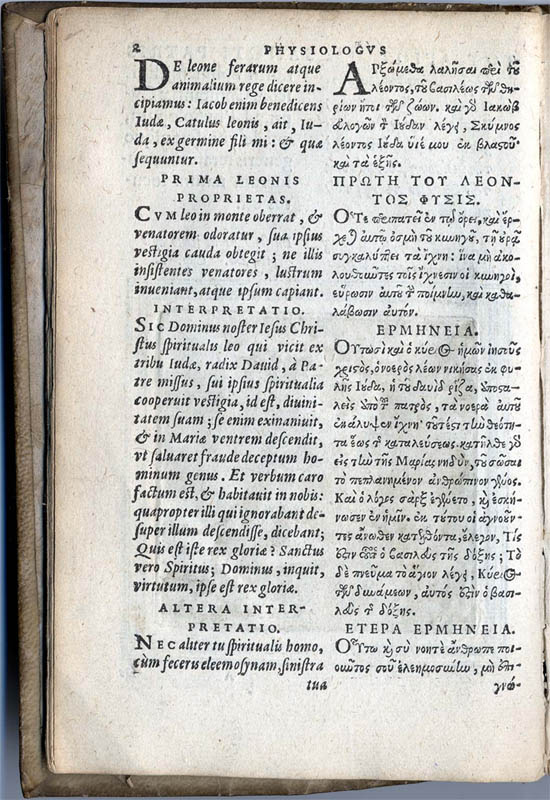

Lion in the Greek manuscript of the Physiologus (see below), made in Venice in the early 16th century, which in 1587 come from the property of the great Hungarian humanist and doctor Johannes Sambucus (János Zsámboki) to the Viennese Imperial Court Library (today Austrian National Library) (Cod. Phil. Gr. 290)

Lion in the Greek manuscript of the Physiologus (see below), made in Venice in the early 16th century, which in 1587 come from the property of the great Hungarian humanist and doctor Johannes Sambucus (János Zsámboki) to the Viennese Imperial Court Library (today Austrian National Library) (Cod. Phil. Gr. 290)The lion’s tail came here, or rather into the chapter on bestiaries of Eco’s new book, from the Physiologus. The Physiologus was a Greek-language compilation from the second to third century AD, which was translated into several languages, and became one of the bestsellers of the Middle Ages and the forefather of all bestiaries. It described forty animals, plants and minerals, still on the basis of the Hellenistic tradition, but already interpreted in Christian spirit. Eco mentions an example:

| Dopo avere descritto questi esseri, il Fisiologo mostra come e perché ciascuno di essi sia veicolo di un insegnamento etico e teologico. Per esempio il leone che, secondo la leggenda, cancella le proprie tracce con la coda per sottrarsi ai cacciatori, diventa simbolo di Cristo che cancella i peccati degli uomini. | After describing them, the Physiologus also explains how and why each of them carries some ethical and theological teaching. The lion, for example, which erases its own footprints with the tail, so as to hide from the hunters, becomes a symbol of Christ, who erases the sins of mankind. |

An attractive parallel indeed, which connects the signifier with the signified by way of the naive association of “erasing” – just like St. Isidore of Seville does in his Etymologies, so indulgently referred to by Eco –, but which does not further expand the analogy (the footprints of Christ =/= sins of mankind). However, when we open the Physiologus at this place, we read something absolutely different: a fully expanded metaphor, which refers to a Christological doctrine living throughout the whole Middle Ages:

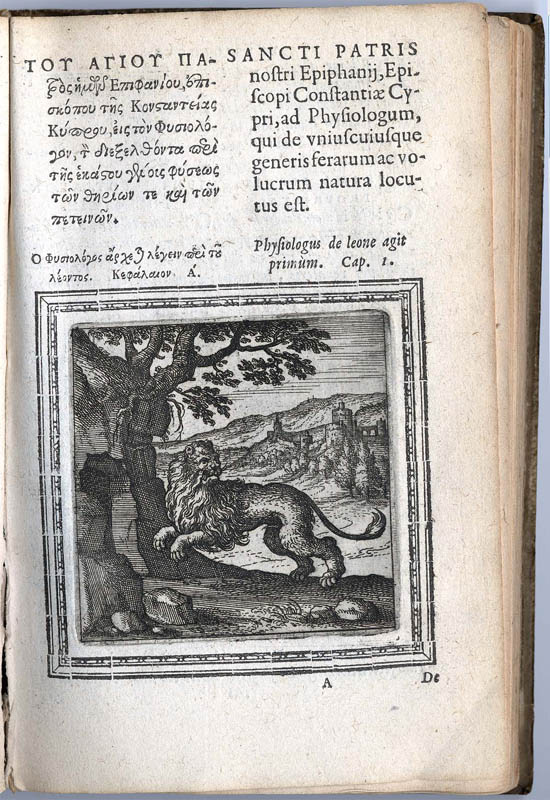

The first two pages on the lion from the 1588 Plantin edition of the Physiologus (the Greek and Latin original of the cited text is on the second page)

The first two pages on the lion from the 1588 Plantin edition of the Physiologus (the Greek and Latin original of the cited text is on the second page)

“When the lion roams the mountains, and he feels the smell of the hunter, he erases his footprints with his own tails, to prevent the hunters following him up, finding his abode, and capturing him … In the same way our Lord Jesus Christ, the spiritual lion … sent by the Father, erased His spiritual footprints, that is, His divinity; He emptied himself, and descended into the womb of Mary to save the deceived mankind.”

The unknown author (identified in the Middle Ages with the fourth-century Bishop of Cyprus and Church Father St. Epiphanius) relates the “scientific observation” accepted from Plutarch and Aelian with a popular theological doctrine which we find in several church fathers – Athanasius, St. Gregory of Nazianzos, Dionysius Areopagita, and even Epiphanius himself – as well as in later writers referring to them: that Christ assumed a human body so as to cheat the devil, the cheater of mankind, who, knowing nothing about His divinity, sought to destroy him as a man and as a (purely human) Messiah, thus actively contributing to His death on the cross and thereby the salvation of mankind.

The theologians recall this great trick with pleasure and by coloring the details. The fourth-century Rufinus of Aquileia, translator of Origen and friend (and later bitter debate partner) of St. Jerome, connects this doctrine with the metaphor of the hook in his commentary on the Apostles’ Creed:

“The object of the mystery of the Incarnation was the divine virtue of the Son of God, as a hook, concealed beneath the form of human flesh. He being found in fashion as a man (Phil 2:8), lured the Prince of this world to a conflict, offering His flesh as a bait. … As a fish seizes a baited hook, it not only does not take the bait off the hook, but is drawn out of the water to be itself food for others. So he, who had the power of death, seized the body of Jesus in death, not being aware of the hook of Divinity enclosed within it, but swallowed it and was caught. The bars of hell being broken apart, he was drawn out as it were from the abyss to become food for others. Ezekiel foretold this under the same figure, saying, ‘I will draw you out with My hook, and stretch you out on the earth. The plains shall be filled with you, and I will set all the fowls of the air over you, and I will satiate all the beasts of the earth with you’ (Ez 29:4-5, 32:3-8). … Job in like manner says in the person of the Lord speaking to him, ‘Will you draw forth the Leviathan with a hook, and will you put your bit in his nostrils?’” (Job 41:1-2)

We see this version of the metaphor in one of the beautiful pieces of thirteenth-century Parisian miniature painting, the Reims Missale (1285-1297) preserved in St. Petersburg, on whose complex iconography I once held an entire semester at the university. On Folio 59v – also an illustration of the Creed – Christ fishing in a boat with Job puts the same question to him, while with the fishing pole hanging in front of the devil He already proves that He does draw forth the Leviathan. And the long scroll of Prophet Oseas, standing to the right, tells us how to understand this: O mors ero mors tua, morsus tuus ero inferne, “oh, death, I will be your death, I will be your sting, oh hell”. Accordingly, this verse became the first antiphone of the Holy Saturday Laudes, the the morning office.

Guillaume Bouzignac (c. 1587 – 1641): O mors ero mors tua, Les Arts Florissants, William Christie

Other times they referred to the trap set to the devil with a different tool. St. Augustine says: “The Lord’s Cross was the devil’s mousetrap, the bait that caught him, the Lord’s death.” This is what we see in Robert Campin’s Mérode Altarpiece (between 1425 and 1428): while in the middle the scene of the Annunciation, that is, of Christ’s incarnation takes place, on the right side St. Joseph is knocking together mousetraps.

Supported by the authority of all this tradition, I have thus changed Eco’s text in the Hungarian translation, carefully erasing the traces of his slip-up:

After describing them, the Physiologus also explains how and why each of them carries some ethical and theological teaching. The lion, for example, which erases its own footprints with the tail, so as to hide from the hunters, becomes a symbol of Christ, who hides His divine nature from the devil.

After the Middle Ages, the motif of Satan cheated by Christ’s human nature and then bitterly disappointed, receded into the background, but hit has not completely disappeared. Its distant echoes can be heard even in so unexpected places, as Carman’s Carman Sunday’s on the way.

| The demons where planning on having a party one night. They got beer and Jack Daniels and pretzels, a little red wine, and some white. They were celebrating how they crucified Christ, on that tree. But Satan, the snake himself, wasn’t so at ease. He took his crooked finger and he dialed the phone by his bed, To call an old faithful friend, to know for sure, that he was dead. He said, “Grave, Grave tell, did my plan fail?” Old Grave just laughed and said, “Oh man, the dude is dead as nails.” Chorus: Well hey, hey, hey on Friday Night, they crucified the Lord at Calvary, But He said, “Don’t dread, in three days, I’m gonna live again, you’ll see.” When problems try to bury you and make it hard to pray, It may seem like Friday night, but Sunday’s on the way! A tranquilizer and a horror flick could not calm Satan’s fear. So Saturday night, he calls up the grave… scared, of what he’d hear. “Hey, Grave, what’s goin’ on?” Grave said, “Man, you called me twice, and I’ll tell you, once more again boss, the Jew’s on ice!” | Devil said “Man grave, do you remember when old Lazarus was in his grave? You said everything’s cool and four days later, BOOM, Ol’ Lazarus, he was raised! Now this Jesus, He is much more trouble than anyone has been to me. And he’s got me shocked, cuz He says, He’ll only be there three!” Chorus Sunday morning Satan woke with a jump, ready to blow a fuse. He was shaking from the tips of his pointed ears, to the toes of his pointed shoes. He said “Grave tell me is He alive? I don’t want to lose my neck!” Grave said, “Your evilness, maintain your cool. You are a wreck!” Grave said, “Now just cool your jets, Big D, my sting is still intact, You see, Jesus is dead forever, he ain’t never coming back, so just mellow out man, just go drink up or shoot up, but just leave old Grave alone, and I’ll catch you la… la… oh no! OH no! OH NO! OH NO… SOMEBODY’S MESSING WITH THE STONE! Then the stone was rolled away and it bounced a time or two, and an Angel stepped inside and said, “I’m Gabriel, who’re you? And if you’re wondering where the Lord is, at this very hour, I’ll tell you he’s alive and well, with resurrection power!” |

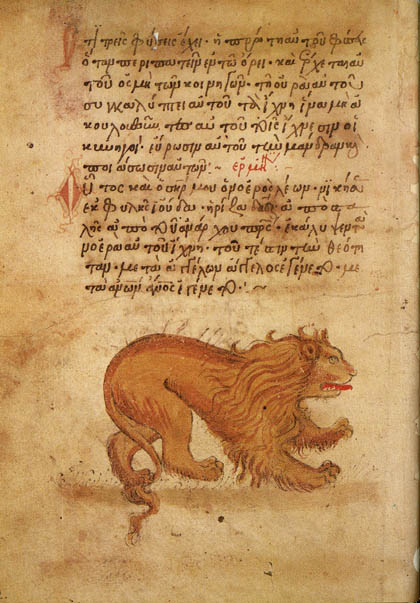

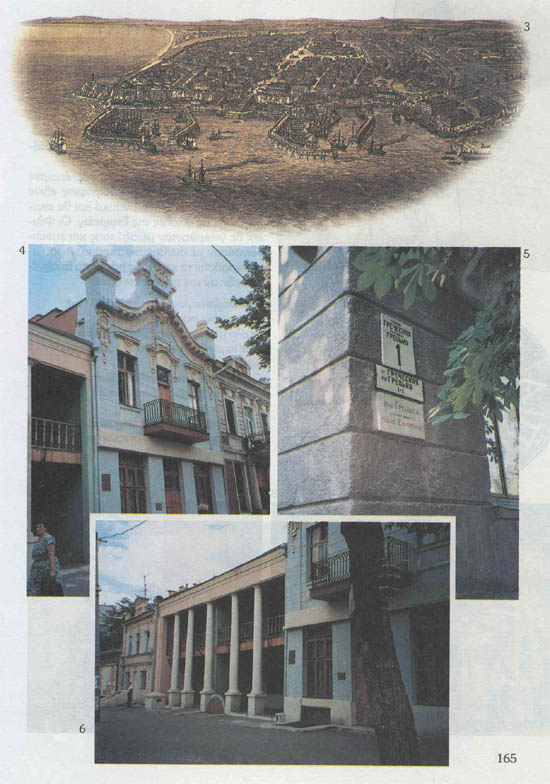

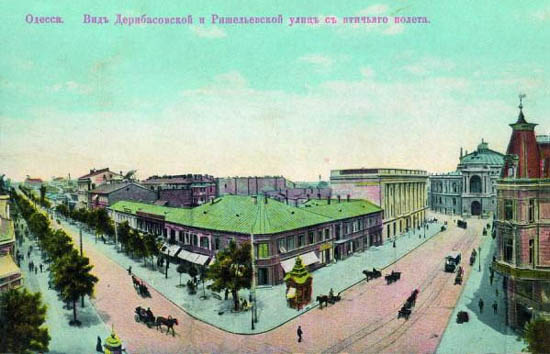

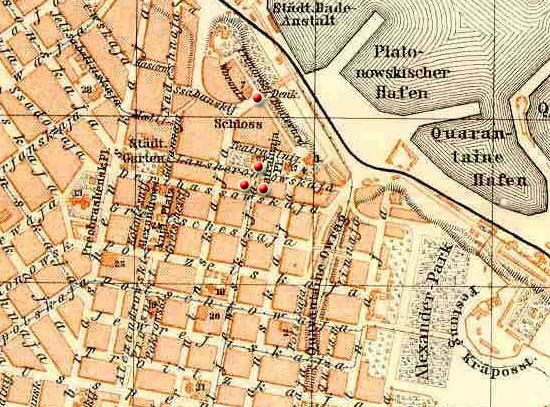

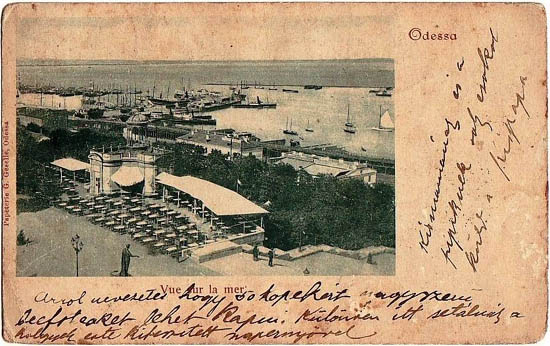

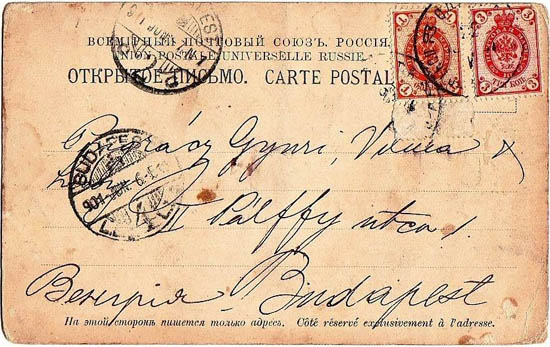

Pausing on Deribasovskaya, at the corner of Rishelievskaya we look around wondering: which was the house featuring in the song? The one to the right when looking toward the suburb was certainly not, because this one, now the building of the National Bank, was the Puritz jewelry house at that time, Odessa’s most elegant fashion store, after which the Odessan language – because there exist a language like this – coined the term bolshoi puritz, ʻa great puritz’ for the most luxuriously dressed playboys. However, the store also owes his fame to the fact that this was the site of the first great success of Sofia Blyuvshtein, that is, Sonyka Golden Hand, the legendarily beautiful and dangerous burglar of the Jewish underworld. In 1883, presenting herself as the wife of a famous Odessan psychiatrist, selected jewels in the value of thirty thousand rubles, and then asked the jeweler to bring them to their flat where her husband would pay for them. The jeweler, drunk with the big business, rushed to the flat, where Sonya opened the door, and taking over the jewels asked him to sit down for a minute in her husband’s study.

Pausing on Deribasovskaya, at the corner of Rishelievskaya we look around wondering: which was the house featuring in the song? The one to the right when looking toward the suburb was certainly not, because this one, now the building of the National Bank, was the Puritz jewelry house at that time, Odessa’s most elegant fashion store, after which the Odessan language – because there exist a language like this – coined the term bolshoi puritz, ʻa great puritz’ for the most luxuriously dressed playboys. However, the store also owes his fame to the fact that this was the site of the first great success of Sofia Blyuvshtein, that is, Sonyka Golden Hand, the legendarily beautiful and dangerous burglar of the Jewish underworld. In 1883, presenting herself as the wife of a famous Odessan psychiatrist, selected jewels in the value of thirty thousand rubles, and then asked the jeweler to bring them to their flat where her husband would pay for them. The jeweler, drunk with the big business, rushed to the flat, where Sonya opened the door, and taking over the jewels asked him to sit down for a minute in her husband’s study.

Opposite the former Puritz store, where now the UniCredit Bank works, was in Utesov’s time one of Odessa’s most elegant cafés, the Fanconi (its namesake opened recently one corner away, on the Yekaterinskaya). This was one of the established meeting places of the Odessan Jewish businessmen, just two blocks from the central synagogue, and it would not have been a really significant institution, had it not been bled for forty-three thousand rubles by Sonya Golden Hand, just one year after the Puritz case. Its long flowering came to an end in 1920, when its best patrons fled from the city, and the Red Army plundered it to the last silver teaspoon. I mean, not exactly. The last silver teaspoon was taken by one of the patrons to America, from where one of its heirs sent it back in 2005 to the newly formed Jewish museum. Today it hangs on the wall of the nearby museum, in the foreground of the archive photo of Café Fanconi, enlarged to life-size.

Opposite the former Puritz store, where now the UniCredit Bank works, was in Utesov’s time one of Odessa’s most elegant cafés, the Fanconi (its namesake opened recently one corner away, on the Yekaterinskaya). This was one of the established meeting places of the Odessan Jewish businessmen, just two blocks from the central synagogue, and it would not have been a really significant institution, had it not been bled for forty-three thousand rubles by Sonya Golden Hand, just one year after the Puritz case. Its long flowering came to an end in 1920, when its best patrons fled from the city, and the Red Army plundered it to the last silver teaspoon. I mean, not exactly. The last silver teaspoon was taken by one of the patrons to America, from where one of its heirs sent it back in 2005 to the newly formed Jewish museum. Today it hangs on the wall of the nearby museum, in the foreground of the archive photo of Café Fanconi, enlarged to life-size.

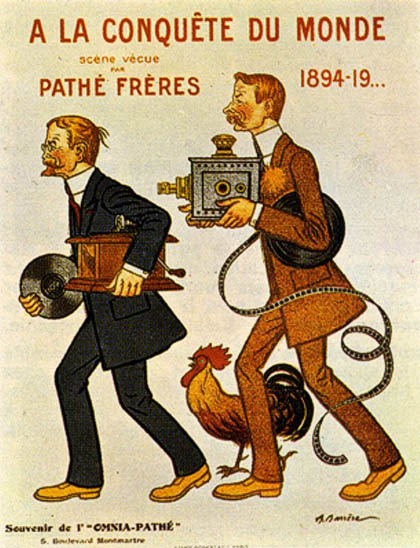

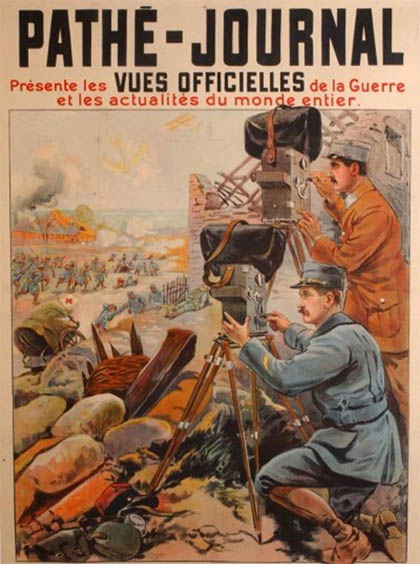

At the third corner, towards the city center, there stands a two-storey house built in 1886, which is called “Clock House” after its former tower-clock. However, its real fame came from the fact that here worked the Odessan office of the Pathé brothers, the largest film distribution company in Odessa. The four Pathé brothers founded their company in Paris in late 1896, one year after the Lumière brothers invented the film. In the early 20th century it became the world’s largest movie machinery and film producer and distributor, and one of the largest phonograph record producers. They introduced the newreels in 1908. Shortly after the turn of the century, they already had seven subsidiary companies in Russia, beginning with Odessa, where the first movie theater – iljuzion – of Russia had been opened already in June 1896 by an agent of the Lumière brothers, and where

At the third corner, towards the city center, there stands a two-storey house built in 1886, which is called “Clock House” after its former tower-clock. However, its real fame came from the fact that here worked the Odessan office of the Pathé brothers, the largest film distribution company in Odessa. The four Pathé brothers founded their company in Paris in late 1896, one year after the Lumière brothers invented the film. In the early 20th century it became the world’s largest movie machinery and film producer and distributor, and one of the largest phonograph record producers. They introduced the newreels in 1908. Shortly after the turn of the century, they already had seven subsidiary companies in Russia, beginning with Odessa, where the first movie theater – iljuzion – of Russia had been opened already in June 1896 by an agent of the Lumière brothers, and where

Looking towards the city center from Deribasovskaya, the Theater Square opens before us. The square is named after the Opera and Ballet Theater, built in its center in 1887 by the Viennese duo of star architects, Fellner and Helmer. Thus the building has a relationship to the Comic Theater in Budapest, designed by them. The two-storey high arch of the facade, which is common in both buildings, was a hallmark of the Viennese architects, adopted in more than forty public buildings designed by them throughout Europe. But the predecessor of the theater dates back to the times of Duke Richelieu. It is a signal of Odessa’s cosmopolitan culture and its European level that less than fifteen years after its foundation, in 1810 there was already a huge demand for an opera house. Prince Vorontsov ordered the revenue of the port quarantine, paid by the ships stationed there, for the maintenance of the opera house, and as the chief medical officer of the quarantine was also a shareholder of the opera as well as a passionate opera fan, and so when he saw it necessary, he ordered a long-term general quarantine in the port. The extra income was used to invite some great European singers every year, and the Odessa Opera has retained its fame up to this day.

Looking towards the city center from Deribasovskaya, the Theater Square opens before us. The square is named after the Opera and Ballet Theater, built in its center in 1887 by the Viennese duo of star architects, Fellner and Helmer. Thus the building has a relationship to the Comic Theater in Budapest, designed by them. The two-storey high arch of the facade, which is common in both buildings, was a hallmark of the Viennese architects, adopted in more than forty public buildings designed by them throughout Europe. But the predecessor of the theater dates back to the times of Duke Richelieu. It is a signal of Odessa’s cosmopolitan culture and its European level that less than fifteen years after its foundation, in 1810 there was already a huge demand for an opera house. Prince Vorontsov ordered the revenue of the port quarantine, paid by the ships stationed there, for the maintenance of the opera house, and as the chief medical officer of the quarantine was also a shareholder of the opera as well as a passionate opera fan, and so when he saw it necessary, he ordered a long-term general quarantine in the port. The extra income was used to invite some great European singers every year, and the Odessa Opera has retained its fame up to this day.